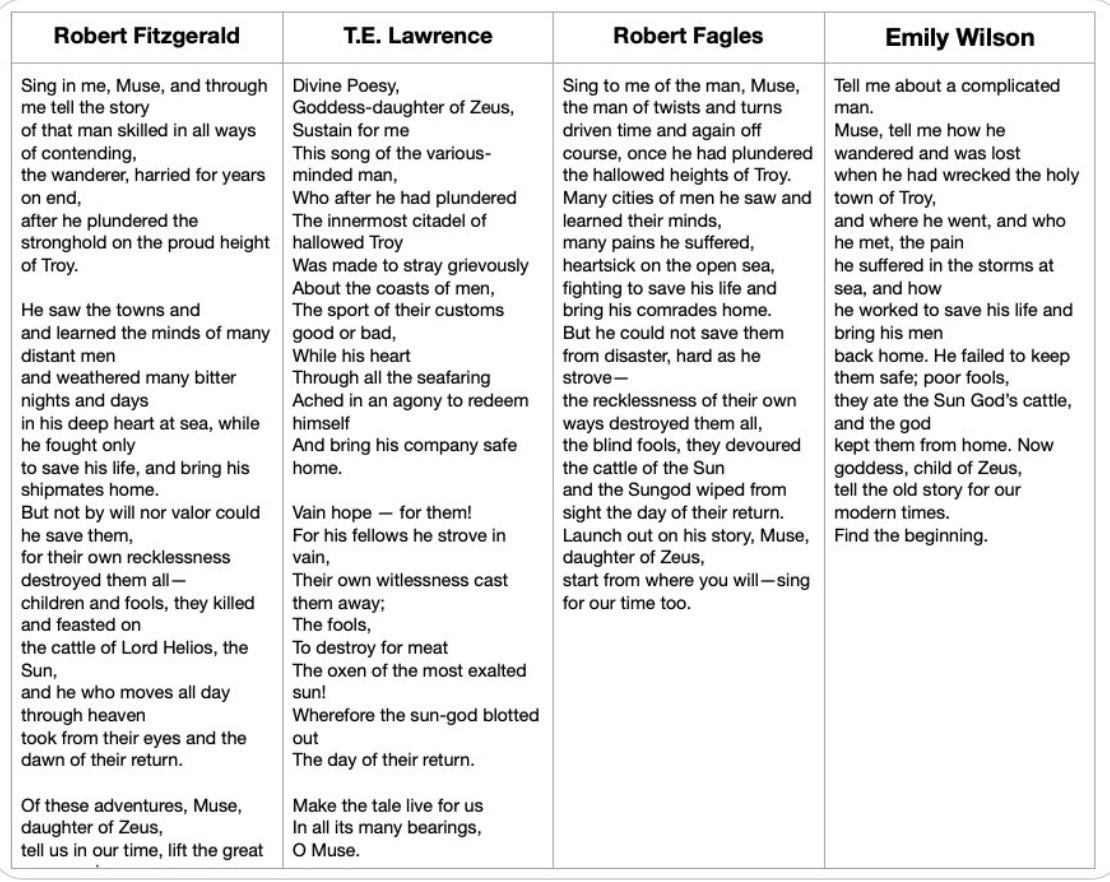

This selection of four translations of the first ten lines of the Odyssey (the "proem", as it's known among Homerists) has done the rounds online. So I wanted to write up some notes on the specific choices of each of these translations in relation to the Greek. My goal is not to rank them, nor to criticize my esteemed predecessors and colleagues, but to analyze in a more precise way, for the benefit of those who have not read the original, how each of these pieces of English echoes and differs from the Greek (as every translation must do).

Note there are plenty of other interesting Homer translations out there. You may get a better sense of the range in English translation approaches if you also look at one of the older ones in rhyming couplets (like C17 George Chapman, or C18 Alexander Pope, both of which are great), and one of the modern free verse ones that use more archaic and "foreignizing" word order (Richmond Lattimore’s or Caroline Alexander’s), and one of the prose ones (like Samuel Butler or E. V. Rieu, both interestingly odd translations of this great poem). But you can also learn a lot by looking at any random selection of translations of the same passage – it's always an enlightening exercise.

The online-circulated version cuts off the end of Fitzgerald and the lineation is unclear, so here are those important and beautiful lines:

Of these adventures, Muse, daughter of Zeus,

tell us in our time, lift the great song again.

Here is the Greek for this same passage:

ἄνδρα μοι ἔννεπε, μοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς μάλα πολλὰ

πλάγχθη, ἐπεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσεν:

πολλῶν δ᾽ ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω,

πολλὰ δ᾽ ὅ γ᾽ ἐν πόντῳ πάθεν ἄλγεα ὃν κατὰ θυμόν,

ἀρνύμενος ἥν τε ψυχὴν καὶ νόστον ἑταίρων.

ἀλλ᾽ οὐδ᾽ ὣς ἑτάρους ἐρρύσατο, ἱέμενός περ:

αὐτῶν γὰρ σφετέρῃσιν ἀτασθαλίῃσιν ὄλοντο,

νήπιοι, οἳ κατὰ βοῦς Ὑπερίονος Ἠελίοιο

ἤσθιον: αὐτὰρ ὁ τοῖσιν ἀφείλετο νόστιμον ἦμαρ.

τῶν ἁμόθεν γε, θεά, θύγατερ Διός, εἰπὲ καὶ ἡμῖν.

Here are some comments on the idiosyncratic version by T. E. Lawrence (1932, yes, he of Arabia), simply as a rendition of the Greek. First: none of the first two lines corresponds to anything in the Greek in that place. The original identifies the Muse as the goddess daughter of Zeus in line 10, not line 1, and the phrase "divine poesy" is a modern concept, not in the Greek (a poem with real goddesses doesn't need divine poesy). "Sustain" is an interesting rendition of a verb that just means "say" or "tell" (ἔννεπε) – did Lawrence worry his attention might flag in such a long project? "Various-minded" adds an element that is not in the original: the word πολύτροπον suggests multiplicity (πολύ-, as in "poly-gamy" or "poly-theism"), but also "turns" or "disguises" or "twists"; there's no direct reference to Odysseus' famous mind, although Lawrence, like many other translators (notably Pope, who adds "wisdom") feels it's so essential to the brand of our beloved hero that it has to be plugged in even when Homer has failed to mention it. There are several other interesting additions: "coasts" (in fact Odysseus goes inland in several of his visits to exotic locations); "good or bad" (Homer isn't moralizing in this way); "sport" (Lawrence prided himself on his athleticism); "to redeem himself" (sounds weirdly modern); "ached in an agony" is far more redundant than the original; the repetition of "vain" doesn't correspond to anything, though it establishes a moralizing tone; "for meat" gives us a motive that the Greek doesn't quite have (they ate, but we aren't told why); "most exalted" again tries to explain what is resonantly unexplained in Homer; the last two lines are mostly made up by Lawrence. Perhaps the prosaic "in all its many bearings" is a way to acknowledge that πολύτροπον could also refer to the poem as well as to the protagonist. A final interesting feature of the Lawrence is that he includes this florid free verse preamble, and then does the rest of the translation in prose, and even refers to Homer's great poem as a "novel". It's the Odyssey for lovers of H. Rider Haggard. For what it's worth, nine year old me adored King Solomon's Mines.

Here are some comments on the Robert Fitzgerald (1961) as a rendition of the Greek. It’s in largely-iambic verse, although with many variations: the final line has six beats and is largely trochaic, not iambic. The "in me... through me" thing is lovely but completely made up by Fitzgerald. The translation is very expansive, such that the two Greek words ἄνδρα ... πολύτροπον are rendered by 11 English words: "the story/ of that man, skilled in all ways of contending". The"ways of contending" phrase is more resonant than informative (unclear how the idea of "contending" can be got out of the Greek, though of course it is fine as a description of one of Odysseus' big specialties). Additions corresponding to nothing include: "proud", "distant", "by will nor valor" (love it, but it's not in the Greek), "killed and", "Lord", "he who moves all day through heaven" (again, love it but it's a total invention), the "took from their eyes" thing (nothing about blinding in the Greek, but it's a great phrase), "adventures" (a very modern idea of what the Odyssey is about), and "lift the great song", another lovely phrase that doesn't correspond to the Greek (no lifting, no great song -- this is Fitzgerald beautifully borrowing the language of the KJV Psalms and importing it to an entirely different ancient text). For what full disclosure, I often like Fitzgerald more as English verse than many other twentieth century American translations, because he's attuned to rhythm in English in ways that most modern classicists sadly are not. At the same time, the fine literary artfulness can feel out of keeping with the oral poetics of the original; to me, it's more suitable for Vergil than Homer. Moreover, as you can see here, Fitzgerald is often a very long way from the Greek, even on the boring but demonstrable level of what the Greek actually says, or doesn't say. Fitzgerald’s translation is much longer than the original, largely because it adds a lot that isn’t there in Homer.

Here are some comments on the unmetrical American free verse by Robert Fagles (1996). It's enjoyable, very loud and lively and often chatty, so it's not surprising that it has remained a popular favorite and bestseller in the US. It makes Homer into easy reading. Fagles is often very expansive, including repetitions where the original doesn't repeat ("the man... the man"), and frequently giving a little extra pep by adding contemporary American idioms that make this alien poem feel familiar: "twists and turns", "time and again", "off course" (an added nautical metaphor, as kind readers have pointed out to me!), "heartsick", "wiped out from sight" (borrowing from Fitzgerald). None of these metaphors are in the original. Fagles often amps up the emotional stakes, adding melodrama or sentimentality that isn't in the Greek: so we have for instance "devoured" as a translation for the normal word for "eat" (ἤσθιον). Similarly, a favorite Fagles word is "disaster" (which corresponds here to nothing in the Greek but recurs frequently in Fagles: he reminds us constantly that the stakes are high). I like the use of "sing" at beginning and end of the passage – nice ring composition – but the Greek ἔννεπε... εἰπὲ suggests say (not "sing", which is a different verb). "Blind fools" introduces a metaphor that isn't in the Greek (νήπιοι are "fools" or "childish", but not literally or metaphorically "blind") -- again, you can see Fagles' debt to Fitzgerald. I like "launch out" for the embarking of the poem, but it's entirely made up by Fagles (no ship metaphor in the original). More substantially, it's very debatable to add "his story" for words that more literally suggest "of these things": Fagles frames the whole poem as the story of a single individual, "him", which the Greek doesn't do (and instead, the Greek shows us the intertwining of several distinct people's stories, including the successful and unsuccessful nostoi). Finally, the Greek καὶ ἡμῖν literally suggests "also to us": Fagles has borrowed "our time" from Fitzgerald. That is fine! I'm sure Fitzgerald didn't mind. But it's worth seeing that these different translators are not always independent from each other: features that aren't in the Greek can be replicated from one translation to another. For what it's worth, I've taught Homer in translation quite frequently over the decades, as well as in the original, and tried out a number of different translations. I've found my students often prefer Fagles to Fitzgerald. They both domesticize quite radically and add a lot that isn't exactly there in the Greek, but Fitzgerald took tips from Ezra Pound and created an artful, allusive, almost Poundian Homer, whereas Fagles is more Whitmanesque: It's Intense!... With typography! It's Epic! So it fits with American twentieth century assumptions about what “epic” means.

The final one is mine, Emily Wilson (2017, regular iambic pentameter). I wanted to recreate certain alien features of the original that aren't reflected in most modern translations, including these three cited here. Those features include, most obviously, very regular, very traditional poetic meter. The original is dactylic hexameter, the traditional meter of narrative verse in archaic Greece, so I used the anglophone equivalent, iambic pentameter. If you can't hear meter in English on the page, which is quite common because many people have not had enough practice reading metrical verse, just try reading it out loud (as Homer was experienced in antiquity), and you'll hear the beat. I also prioritized the pacing of the original: I stuck to the same number of lines as the original, wanting to avoid the temptation to expand as most of my predecessors had done. Moreover, I wanted to echo other poetic/ sonic features of the original, such as alliteration (πολύτροπον... πολλὰ...πλάγχθη, ἐπεὶ ..πτολίεθρον ἔπερσεν:/πολλῶν: "wandered... was... where... went.", "me... man...Muse").

I wanted in general to evoke the energy and clarity and beauty and music and pacing of the original, avoiding both the flatness or awkwardness of the more "literal" versions (the ones like Lattimore that prioritize the syntax or word order of the original rather than its style or tone), and the looser ones that tend to expand or riff on the original (like these three).

I tried to think hard about how similar effects might be achieved by different linguistic means: so for instance, it's impossible to start an English sentence with the object ("man", andra), unless you repeat it (as Fagles does) – but I did not want to introduce extra repetititions if possible – so I put "man" in the emphatic position at the end of the line, rather than emphatically at the beginning, to try to create a similar effect by different means.

I tried in general to avoid adding extra metaphors or adorning the narrative with modern English idioms, as these other translators have done. Hence, my translation may seem stark, compared to those that have added a lot that isn’t paralleled by the original – but that perception depends on a comparison with other translations, rather than with the Greek. I will write another post about more of my specific word choices. People ask endlessly about “complicated”, and I have things to say about that. For now, I will note only that translation, even more than most writing, takes dozens or hundreds of drafts, even when it's a text or poem you've been reading in the original for decades before you even begin to consider how to English it. There’s no such thing as “the” right answer, and numerous different translations, including all of these, can provide valid but different portraits of the original. I hope my translations bring readers to engage in new ways with the complexities, humanity and depth of Homer.

Note, for those sensible people who are untainted by twitter: this screenshot of the beginning of four translations, including mine, was circulated by a number of accounts that primarily seem to focus on promoting hatred of various kinds. Many of them posted it explicitly as a demonstration that women can't or "shouldn't be allowed to" translate Homer, and the predictable pile-on ensued. Nothing new. Many people and robots apparently have strong feelings about what I look like, which is apparently relevant for assessing my work. The same screenshot was reposted from these accounts by a number of my dear classicist colleagues, as the basis for a supposedly neutral discussion of "which translation is best". Most of those engaging in the discourse, from both groups, seemed to have little or no interest in discussing the specific relationship of the translations to the Greek. To me, that's a problem. There is, of course, no benefit to feeding all this nonsense. But I also know that many instructors and students read Homer and other ancient texts in translation, and are interested in the work of translation and in comparisons between translations and the original, about which I have many thoughts. So here I am on Substack. Thank you for being here and for reading.

Thank you to everyone who pointed out "off course" is likely an implicit sailing metaphor. I am not sure if Substack lets one edit but I should fix that if so. The addition of extra nautical language fits with Fagles' use of "launch", another nautical metaphor that isn't in the Greek. Both those added metaphors fit with the general tendency of the Fagles translation to bring the Odyssey a little closer to what modern readers expect it to be - including the idea that it's primarily a narrative about difficult sea voyages. I'm grateful for the close reading!